Money Ballers — The Largest Sporting Brands on Earth

Published 09-JUN-2017 15:20 P.M.

|

9 minute read

Whether you’re tuning in to Aussie rules footy via free-to-air TV, or catching up with European leagues in the early hours of the morning – courtesy of your Optus subscription — brands, sponsors, advertising and marketing lures are literally everywhere.

And with two major soccer teams – Brazil and Argentina – gracing the Melbourne Cricket Ground tonight, it’s a timely reminder of the importance of branding in sports.

Even at pitch-side, you can’t escape brand prominence: branding takes space on players’ shirts, in the stands, on the stadium itself, on the match programme and the bewilderingly scaleable world of online shopping, of course.

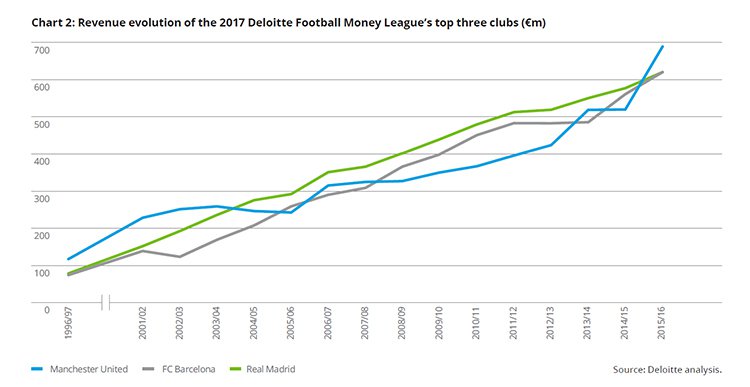

If looking at the niche of football, lovingly endeared as ‘soccer’ by the vast majority of nations globally, the current rate of financial growth has reached parabolic levels, with the largest brand in football now estimated to be worth almost $2 billion.

Real Madrid, current European champions and considered the best football team in the world in terms of success on the field, has also taken top spot in the financial stakes, pipping Manchester United into 1st place as the ‘largest brand in football’.

The relative differences in scale between what football (soccer) as an industry is now worth, compared to what it was worth in the past, (and then comparing with other sporting revenue-churners such as Australian Rules football, American Football etc.) dwarfs the others by comparison.

Comparison with AFL

For starters, there are only 20 or so American Football or Australian Rules Football teams in the professional ranks. In soccer, the number of professional clubs where players are earning full-time salaries, stretches into the thousands.

This could explain how the top 10 clubs in soccer generate a cumulative sum of almost $10 billion per year in revenue. By comparison, if you combined every Aussie Rules team into a single entity, its gross revenue would barely exceed $500 million per year.

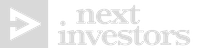

The largest Aussie rules team, as measured by its ability to generate revenue, is Collingwood (the Magpies) with an annual revenue of AU$71.5 million (US$50 million). By comparison the largest soccer team by revenue generates around US$700 million per year — making the largest soccer brand (Real Madrid) more valuable than the largest Aussie rules brand, by a factor of 10.

Further afield in the United States, there is similar largesse to be found in the American version of large sporting brands, spread across several major sports including basketball, football, ice hockey and baseball.

Each sport has its large and small teams, with the largest teams expecting to earn anywhere between $20 million – $200 million per year in revenue, depending on the team.

How do sporting brands, and football as the largest stakeholder, earn all this cash?

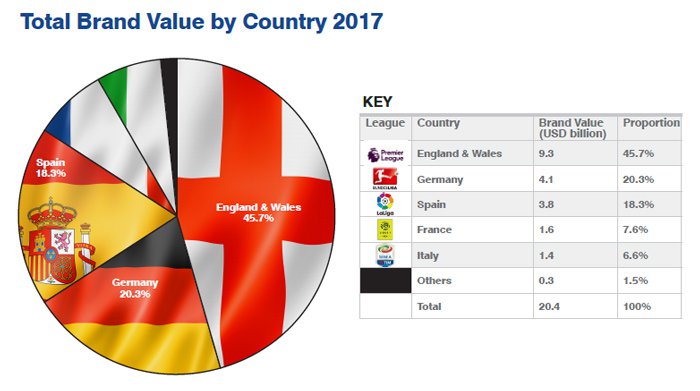

In terms of attendances, every major team in any country can easily pull in 50,000+ for a match event each week. But where British and European soccer teams are excelling is in convincing the world’s sporting public to track, watch and ultimately ‘consume’, the UK-based Premier League entertainment product, in favour of others.

German and French clubs have similar addressable audiences, even lower ticket prices and their people are just as interested in football, as any Aussie, Yank or European — but English clubs earn around 3 times more on average.

The top 10 footballing brands are the following:

From the top 10, six clubs are British.

Manchester United is the top revenue-generating club, although in terms of the team’s success, it has been struggling for league position and success since the departure of their greatest manager Sir Alex Ferguson in 2013, after a 27 year stint at the club (a rarefied record in itself).

In football, it’s not necessarily the team’s performance that decides the club’s overall success. This is because the success of a football team is now measured in such a variety of ways, using such a wide-ranging scope of observational criteria, that it is often difficult to define what actual ‘success’ entails.

For average fans, success is seeing their team winning trophies, finishing at the top of league rankings and being considered the best ‘team’. For many of football’s corporate elite and managerial decision-makers, ‘success’ looks a little different. For them, how many tickets were sold, at what price and how many different nationalities/territories and audiences are buying their merchandise, are more pertinent questions than whether their team has won one European Cup or five.

Evaluating the value of brands

One way of measuring football brands (and sporting brands in general) is to not only focus on one metric or another. There is a more holistic way.

Valuation and strategy consultancy Brand Finance conducts an annual study, calculating the power and value of the world’s leading football club brands.

A brand’s power/strength is assessed (based on metrics such as stadium capacity, squad size and value, social media presence, on-pitch performance, fan satisfaction, fair-play rating, stadium utilization, and revenue) to create a ‘Brand Strength Index’ (BSI) score out of 100.

This is used to determine what proportion of a business’s revenue is contributed by the brand, which is projected into perpetuity and discounted to determine the brand’s value. The Brand Finance Football 50 report is the first of any kind to take into account the full sporting results of the 2016/17 season.

Despite being football’s most powerful brand, in terms of brand value, it still trails Manchester United by a considerable margin. United, despite finishing a disappointing 6th in the Premier League, is the most valuable brand in football, worth US$1.8 billion to Real’s US$1.5 billion. The most crucial ingredient has been the club’s commercial nous and ability to convert its success into lucrative deals across dozens of industry sectors and national territories.

Revenue-generation

Football clubs will typically utilise anything at their disposal to raise revenues. This includes marketing the actual ‘team’ and all its players as much as commercially possible.

To illustrate the breakneck speed with which money is dominating football as a sport, consider Arsenal’s sponsorship deal in 2004.

Arsenal agreed to have its stadium named ‘Emirates Stadium’ after being offered $150 million for 15 years by Emirates Airlines, a Middle-Eastern airline carrier. The fee was simply to have its brand name on the stadium in bright lights for 15 years. On top of that there’s cash for shirt sponsorship, memorabilia, merchandise, ticket sales, TV revenue-sharing, media spin-offs, online on-demand content and the list goes on.

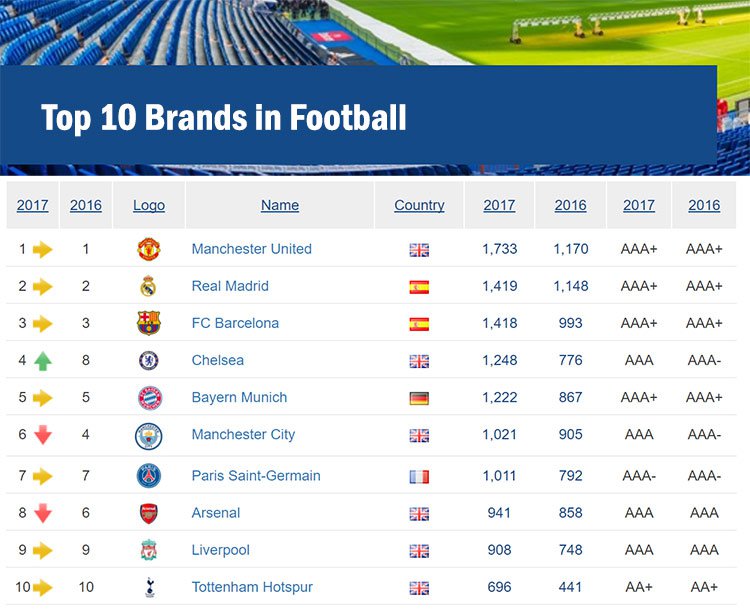

The prime sources of income for all sporting brands are roughly similar (match-day sales, broadcasting cashflow and commercial agreements), and all of these revenue streams are growing year-on-year, according to Brand Finance.

TV deals

There are few better bargaining chips than live sport, which is why the battle for live football viewing rights has never been more fierce, in Europe or anywhere else.

BT Sport paid £1.18bn (A$1.6bn) to secure exclusive rights for Champions League and Europa League football for 4 years. There are around 20-30 Champions league games and 20-30 Europa Leagues matches per year, so BT effectively paid around AU$50 million per match.

The deal certainly raised the bar, and not surprisingly the company has already announced its third price hike in 18 months, not only for its sport broadcasting services, but also other services such as broadband and telephony services. Aussie-dwelling Optus has faced similar dilemmas after winning Premier League broadcasting rights in Australia last year.

Player transfers

Player transfers in football have been growing exponentially for more than two decades. The current world record transfer fee for a football player is €105 million (A$155 million) paid by Manchester United to Juventus in 2016, for Paul Pogba, a 23 year-old French international.

Beyond what’s listed above, additional revenue-generators for soccer brands are sponsorships, ticket sales, merchandise, capital injections and prize money

Not forgetting China

Much like it has done so in the world of international commerce and finance, China is raising its head as a serious contender for sporting dollars in football.

Over the past 5-10 years, the Chinese effect upon soccer has been unprecedented. From a point of having almost no national league or market to speak of, it is now routine to see Chinese clubs steal away some of Europe’s best players, and offer salaries in excess of what Real Madrid, Barcelona or Manchester United could afford.

Shanghai SIPG agreed to pay £58million (A$100 million) for Oscar, while Shanghai Shenhua paid an undisclosed sum to Boca Juniors for Carlos Tevez. Oscar, Chinese football’s most expensive signing to date, earns AU$750,000 per week in Shanghai.

So, while the differences in team and club size can reach up to x10 – the differences in player salaries can easily reach x100, compared to what other sports offer.

Which European team is most China-orientated?

None other than German-based Bayern Munich.

The forward-thinking Germans have taken the lead by being the first Western team to open its fully-fledged club representative office in China.

Its new Shanghai office is the first of any European football club to open in mainland China.

Bayern Munich has also launched two football schools in Qingdao and Shenzhen this year, which has increased the brand’s familiarity among young players, as has its intensive investment in social media.

Bayern’s hard work is paying off. Brand Finance’s research shows that the club has a very strong presence in China, while the Bundesliga (generally less widely broadcast than La Liga or even Serie A) is China’s most watched foreign competition after the Premier League.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has a golden vision for football in China, and is ensuring the Government plays its role in driving the Super League revolution. The President has set out a 10-year plan, running from 2015 to 2025, to double the size of the Chinese sports economy to more than £600billion, based on state and private investment in football.

The aim is to produce 100,000 players by ploughing money into grassroots football and creating 20,000 new ‘football schools’ and 70,000 pitches by 2020, thereby turning China into a footballing superpower.

Currently, China is 83rd in FIFA rakings, sandwiched between Antigua and the Faroe Islands.

In its entire history, China has only appeared at a World Cup once — playing three matches, losing them all and not scoring a single goal – so there’s certainly room for improvement.

Tonight, soccer will be closer to home

For Aussie soccer fans in and around Melbourne today, you can catch a glimpse of some of the world’s best paid and most successful players, as Brazil plays Argentina at the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) – there’s no such things as “friendlies” when these two teams take the field.

The game will showcase both teams’ most ‘valuable’ players including Lionel Messi (Barcelona & Argentina).

If you don’t want to fork out the A$225 ticket price, you can always watch it for free on Channel 9.

Just mind the adverts.

General Information Only

S3 Consortium Pty Ltd (S3, ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘our’) (CAR No. 433913) is a corporate authorised representative of LeMessurier Securities Pty Ltd (AFSL No. 296877). The information contained in this article is general information and is for informational purposes only. Any advice is general advice only. Any advice contained in this article does not constitute personal advice and S3 has not taken into consideration your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Please seek your own independent professional advice before making any financial investment decision. Those persons acting upon information contained in this article do so entirely at their own risk.

Conflicts of Interest Notice

S3 and its associated entities may hold investments in companies featured in its articles, including through being paid in the securities of the companies we provide commentary on. We disclose the securities held in relation to a particular company that we provide commentary on. Refer to our Disclosure Policy for information on our self-imposed trading blackouts, hold conditions and de-risking (sell conditions) which seek to mitigate against any potential conflicts of interest.

Publication Notice and Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is current as at the publication date. At the time of publishing, the information contained in this article is based on sources which are available in the public domain that we consider to be reliable, and our own analysis of those sources. The views of the author may not reflect the views of the AFSL holder. Any decision by you to purchase securities in the companies featured in this article should be done so after you have sought your own independent professional advice regarding this information and made your own inquiries as to the validity of any information in this article.

Any forward-looking statements contained in this article are not guarantees or predictions of future performance, and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond our control, and which may cause actual results or performance of companies featured to differ materially from those expressed in the statements contained in this article. S3 cannot and does not give any assurance that the results or performance expressed or implied by any forward-looking statements contained in this article will actually occur and readers are cautioned not to put undue reliance on forward-looking statements.

This article may include references to our past investing performance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of our future investing performance.